Why Did the European Private Company Fail?

An EU-wide legal form could be transformative for start-ups. Yet the last reform stalled. To revive it, we need to understand why.

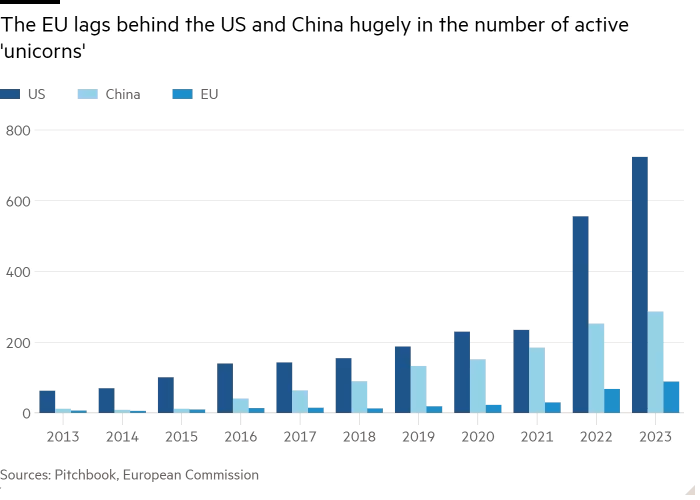

It is no secret that it is easier to scale an American start-up than a European one. Next to far better access to venture and human capital, less overhead, and favorable taxation, one advantage of the US is Delaware General Corporation Law. Delaware became the top choice for tech companies by offering a business-friendly legal framework and the ability to operate seamlessly across all 50 states. The European 'single market' with its 27 countries—and legal frameworks—does not offer the same simplicity.1 This legal fragmentation creates costly friction for cross-border growth, which is particularly important for start-ups that need to scale rapidly to survive. As a result, 30% of EU-founded unicorns have relocated abroad over the past decade, with most moving to the United States.2

Fixing this broken pipeline from ‘invention to commercial success’ is a core theme of Mario Draghi's recent report, which proposes a bold policy agenda to close Europe’s economic gap with the US and China.3 To overcome legal fragmentation, it recommends an EU Inc. for start-ups:

Finally, the EU should support rapid growth within the European market by giving innovative start-ups the opportunity to adopt a new EU-wide legal statute (the "Innovative European Company"). (…) These companies would have access to harmonised legislation (...) and they would be entitled to establish subsidiaries across the EU without incorporating separately in each Member State.

This idea isn't new. The EU already tried something similar more than a decade ago. It is barely remembered now because it failed. To revive it, we need to understand why.

How the SPE Got Lost in Legislation

In 2008, the European Commission proposed a pan-European legal form to boost small business: the European Private Company, also called Societas Privata Europaea (SPE). Inspired by Delaware's framework, the SPE included:

Simplified Legal Structure: A single company form across the EU to reduce legal complexity and administrative costs and enable easier cross-border operations.

Flexibility in Internal Governance: Freedom for businesses to set governance rules, including board structure and voting rights.

Minimum Capital Requirements: Minimum capital set at €1, making it accessible and straightforward for start-ups to incorporate.

The reform initially won the backing of the most powerful business lobby groups and economically liberal countries like the UK and the Netherlands. In 2009, the European Parliament passed the proposal with strong backing from the conservative European People's Party and the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe.

When the proposal reached the Council, resistance emerged from Germany, France, and Austria. They were concerned that businesses would use the SPE to bypass their stricter national regulations, particularly on codetermination of workers through corporate boards.4 Essentially, this was about fears of forum shopping, i.e., companies exploiting the SPE to incorporate in EU countries with minimal regulation while competing in stricter markets, potentially triggering a race to the bottom for labor rights. Similar concerns had already delayed the Société Européenne, a common legal form for publicly traded companies, by over 30 years.5 Ultimately, these concerns repeatedly prevented the Council's unanimous approval, prompting the Commission to quietly shelve the SPE in 2014, where it's been gathering dust ever since.6

So far, this has been a familiar story: strong labor traditions and protection of national interests preventing broader economic liberalization of the EU. Yet essential in the bill's death were not just French unions but German conservatives. This is puzzling. Why did the CDU, which famously cares more than anything about Germany's export-heavy small and medium enterprises, block the SPE?

A Story of Internal Divisions

As Germany's last big tent party, the CDU is ideologically diverse, uniting pro-business neoliberals and more pro-labor social conservatives. The former group supported the SPE due to its benefits for Germany's Mittelstand and found support in the parliamentary group. However, Germany's veto in the Council was shaped by the labor-conscious faction and their codetermination and creditor protection concerns.7 They could also point to the recently created mini-GmbH, a simplified version of the German LLC, as a national alternative.8

… and External Pressure

Shifting coalitions in German multi-party politics played a key role. In 2013, the center-left SPD, with its strong ties to labor unions, replaced the pro-business FDP as the CDU's coalition partner. For the SPE, this meant a hardened German position on codetermination and worker's rights.9 This shift aligned with the post-2008 financial crisis era, which led to a backlash against untamed capitalism and heightened regulatory caution in Europe. In such a climate, pushing a reform perceived as deregulatory wasn't going to win political capital.10

A Chance for Revival

In summary, the failure of the SPE was a slow and complex process with an unlikely antagonist. But since 2014, a lot has changed in the political landscape: The focus has moved towards promoting growth and innovation, as highlighted by the Draghi report and the European Council's strategic agenda, which now prioritizes competitiveness and security over the Green Deal. This reflects a growing consensus among experts and policymakers that these priorities are essential to prevent Europe's economic and geopolitical decline.

Germany is under particular pressure to stimulate growth and foster innovation. The CDU, now in opposition and under new leadership, plans to campaign on economic growth and is expected to regain power in fall 2025. With their economic policy platform still evolving, there could be an opening to champion initiatives like an EU Inc. After 2014, some party members and industry groups have voiced support for an SPE 2.0, and it remains politically attractive, boosting growth for the Mittelstand while bolstering the CDU's cherished pro-EU credentials.11

In France, a liberal centrist president has replaced Francois Hollande and will remain in office until 2027. And even if opposition from France, Austria, or Sweden persists, EU procedures now allow for a qualified majority in the Council, making it possible for a new EU Inc. statute to pass with Germany's support.12

The time is ripe for a revival. With renewed political momentum, shifting strategic priorities, and increased buy-in from national governments, Europe has a unique window of opportunity to establish an EU Inc. Let's seize it to become a more attractive place for start-ups and a stronger force for progress in the 21st century!

Finally, a special thanks goes to Rob Tracinski, Emma McAleavy, Jannik Reigl, Andrew Miller, Anton Leicht, and Simon Grimm for their feedback.

“At the SPE-conference in 2008 German entrepreneur Kristina Schunk stated that setting up a subsidiary abroad requires up to 600 working hours of a qualified employee, causing costs of approximately 15.000€; most often a foreign lawyer needs to be involved, being reflected in the budget with 20.000€, not incl. other costs, such as notary duties.” - Source.

“Between 2008 and 2021, close to 30% of the “unicorns” founded in Europe – startups that went on the be valued over USD 1 billion – relocated their headquarters abroad, with the vast majority moving to the US.” - Draghi report

“The problem is not that Europe lacks ideas or ambition. (…) But innovation is blocked at the next stage: we are failing to translate innovation into commercialisation, and innovative companies that want to scale up in Europe are hindered at every stage by inconsistent and restrictive regulations.” - Draghi report

German law mandates that companies with over 2,000 employees allocate nearly half of board seats to union representatives, and one-third to those with 500-1,000 employees.

You heard right. In total, the whole process from ideation to ratification took 45 years.

This was quite a saga, with by countless failed compromises - a prime example of EU deliberation leading nowhere, except to watered-down proposals and frustrated lawmakers.

The government took a hard line on protecting German codetermination, emphasizing it in 2009 (DS16/11955, Frage 31) and insisting in a 2013 statement that the SPE must not dilute domestic standards (DS17/12245, Frage 143). This stance was driven by the CDU, which governed with the FDP then.

The CDU-led economic ministry was skeptical of the SPE in 2008, citing the comparative creditor protection benefits of the mini-GmbH and encouraging its use (DS16/10464, Frage 3). In 2007, CDU sources like this Bundestag speech by Günter Krings argued against the necessity of the SPE, citing low demand and a preference for the mini-GmbH.

This is reflected in their coalition agreement which aims to “ensure that national regulations on co-determination, tax and commercial register law are not circumvented”.

All the talk about “democratization of the economy” likely made codetermination even more salient.

The CDU’s “pro-European” image is important to them, as EU membership is popular in Germany and broadens their appeal to the political center. It could also win them favor in Brussels. CDU politician and Supreme Court President Stephan Harbarth argued that Germany has a “duty to support an SPE 2.0.”

Or with French support against Germany.